Strategy pattern

Introduction

A bit of theory

The Strategy pattern belongs to behavioral design patterns, focusing on organizing the interaction between objects and classes in a program. Other popular patterns in this category include the Observer and Chain of Responsibility patterns.

Published in 1994 in the book "Design Patterns: Elements of Reusable Object-Oriented Software."

It was written by intelligent individuals - Erich Gamma, Richard Helm, Ralph Johnson, John Vlissides.

Essence

Strategy pattern is a coding technique that enables the creation of multiple ways to perform a specific task. This allows us to utilize various approaches to accomplish a task without altering the core code.

Advantages

- Flexibility and Extensibility: the Strategy pattern allows for easy addition of new algorithms or strategies without changing the client code. This makes the system much more flexible and extensible.

- Isolation of Algorithms: each strategy is encapsulated in its own class, simplifying the support and testing of each algorithm individually.

- Reduction of Code Duplication: strategies help avoid code duplication that may arise when different parts of the system use the same algorithms.

- Compliance with SOLID Principles: the Strategy pattern promotes adherence to SOLID principles, such as the Open/Closed Principle, making it easier to modify and extend the system.

- Improved Code Readability: code using the Strategy pattern is often easier to read, as each strategy has its own name and methods, making intentions more explicit.

Disadvantages

- Increased Number of Classes: applying the Strategy pattern may lead to an increased number of classes in the system, especially if there are many different strategies. This can make the code more complex.

- Increased Configuration Complexity: clients may need to know which strategy to choose, increasing configuration and dependency injection complexity.

- Decision Making: client code must determine which of the available strategies to use in a specific situation. This may require additional decision-making logic, complicating the code.

- Dependencies: client code needs to be aware of the existence of different strategies and have access to the corresponding strategy classes. This can violate the Dependency Inversion Principle, as the client becomes dependent on specific strategies.

Examples

Real Estate Sales

For instance, imagine an application for real estate sales with a search and filtering function for properties on a map.

Initially, everything is fine. We've developed functionality for users and got this pretty filter inside some class.

However, then a Product Manager comes and says that we now need to add a search for rental properties. Thus, we have another type of users: renters. For them, perhaps, photos of the apartment are more important to assess its condition. And what we gonna do? Create an another filter.

In the future, there might be a need to enhance the functionality for legal entities, individuals, etc., introducing various features like contract formation. And there can be many such differences. So you easily turn your code as it expands into this:

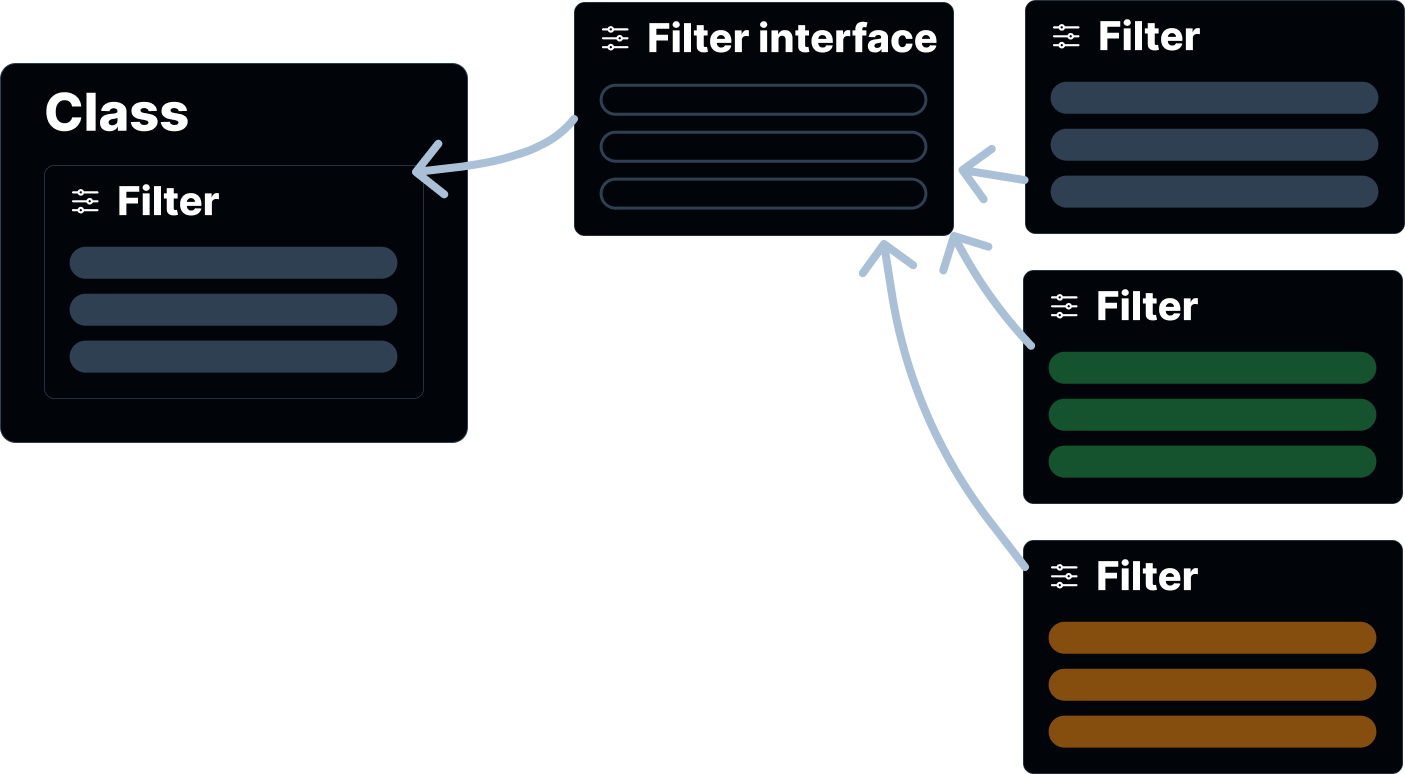

The way out of this problem is precisely the Strategy pattern. And this is how it works. First, we should create an interface that will describe what main class accepts. Then we write some implementations of this interface and can easily switch them right during our program is running.

In a general way, it will looks like this:

And as a big plus, in that case we can create, update and delete filters so much times as we want and it will not break anything in our program, bc the interface will take care of everything, which clearly indicates what is expected from the filter.

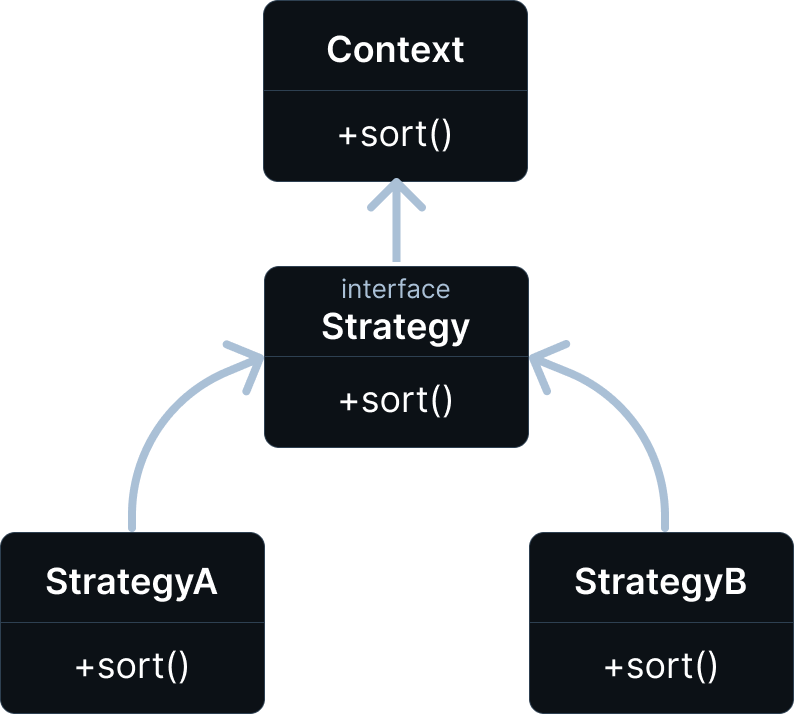

Sorting

And little code example. Let's explore different sorting strategies.

First, let's define the strategy interface:

interface SortingStrategy<T> {

sort(data: T[]): T[]

}Here is a single method, sort, which takes an array and returns it in a sorted form.

Here are three different implementations of this interface:

- Sorting by count

- Sorting by name

- Sorting by price

class CountSortingStrategy implements SortingStrategy<{ count: number }> {

sort(data: { count: number }[]): { count: number }[] {

return data.slice().sort((a, b) => a.count - b.count)

}

}

class NameSortingStrategy implements SortingStrategy<{ name: string }> {

sort(data: { name: string }[]): { name: string }[] {

return data.slice().sort((a, b) => a.name.localeCompare(b.name))

}

}

class PriceSortingStrategy implements SortingStrategy<{ price: number }> {

sort(data: { price: number }[]): { price: number }[] {

return data.slice().sort((a, b) => a.price - b.price)

}

}As you can observe, in each case, a different data type is used, yet the method called is the same.

Now, let's look at the direct implementation:

class Sorter<T> {

private strategy: SortingStrategy<T>

constructor(strategy: SortingStrategy<T>) {

this.strategy = strategy

}

setStrategy(strategy: SortingStrategy<T>): void {

this.strategy = strategy

}

sort(data: T[]): T[] {

return this.strategy.sort(data)

}

}

const data = [

{ name: "Mouse", count: 3000, price: 100 },

{ name: "Monitor", count: 200, price: 30000 },

{ name: "Cabel", count: 900, price: 10 },

]

const sorter = new Sorter<{ name: string; count: number; price: number }>(

new CountSortingStrategy()

)

const sortedDataByCount = sorter.sort(data)

// [{name: Mouse, ...}, {name: Cabel, ...}, {name: Monitor, ...},]

console.log(sortedDataByCount)

sorter.setStrategy(new NameSortingStrategy())

const sortedDataByName = sorter.sort(data)

// [{name: Cabel, ...}, {name: Monitor, ...}, {name: Mouse, ...},]

console.log(sortedDataByName)

sorter.setStrategy(new PriceSortingStrategy())

const sortedDataByPrice = sorter.sort(data)

// [{name: Cabel, ...}, {name: Mouse, ...}, {name: Monitor, ...},]

console.log(sortedDataByPrice)Conclusion

In conclusion, the Strategy Pattern stands out as a powerful and flexible design pattern that empowers software developers to create robust, maintainable, and extensible systems. Through the encapsulation of algorithms into interchangeable components, the Strategy Pattern promotes a clean separation of concerns, allowing developers to modify or extend the behavior of a system without altering its core structure.

By embracing the Strategy Pattern, developers gain the ability to easily introduce new algorithms, adapt to changing requirements, and enhance the overall scalability of their software. This pattern fosters code reusability, as individual strategies can be reused across different contexts, reducing redundancy and promoting a more modular codebase.

Furthermore, the Strategy Pattern contributes to improved testability and maintainability. With each algorithm encapsulated within its own strategy class, unit testing becomes more straightforward, and changes to a specific algorithm have minimal impact on the rest of the system. This decoupling of concerns facilitates a more agile development process, enabling teams to respond quickly to evolving business needs.

In essence, the Strategy Pattern exemplifies the principles of object-oriented design, providing an elegant solution to managing algorithms and promoting a more adaptive and maintainable codebase. As software developers, incorporating the Strategy Pattern into our toolkit equips us with a valuable approach to crafting software that is not only functional but also resilient to change and scalable for the future.